Who was Casanova?

Giacomo Casanova lived from 1725 to 1798. He was born and raised in Venice, later moved to Paris, and lived the last 15 years of his life in Dux – Duchcov in today’s northern Czech Republic. He is famous for his escape from the prison in Venice, but more so for his erotic adventures. His name has become synonymous with Ladykiller, and he’s one of the most famous Italians of all time.

An old man, disregarded by the world and the men and women in it.

The last years of the 18th century. In the Castle in Duchcov in modern-day’s northern Czechia, on the border with Germany, an old man sits at a wooden desk. The room is of considerable size but dark, and the walls are covered with bookshelves from floor to ceiling… It’s the library. The desk is lit by a single candle.

Wrinkled fingers protrude from under the heavy fabric. They’re holding a pen. The man is writing. To his left, full-written pages pile up, and to his right, a stack of white papers are eagerly awaiting the continuation of the story. Despite the crooked shape and the tired posture, the figure is vital and energic. The pen moves quickly and the words fill up the sheets… A river of stories, tales, and myths.

The man is Giacomo Casanova, and what he is writing is his memoirs… A 3700 pages giant book in 12 volumes… Histoire de ma vie – The story of my life. And this book will make his name live forever. He will be remembered as the greatest lover and the most successful seducer of women of all time.

But let’s leave him there in the library before his arthritis gets too painful, and the memory fails him, and go back to Venice, where this extraordinary story begins…

Casanova in Venice 1725 – 1734.

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova was born on April 2, 1725, in Venice. His father was Gaetano Casanova, and his mother was Zanetta Farussi. They were both actors, and little Giacomo’s first years were probably quite interesting with many playful people hanging out with his parents. Remember that at the time, Venice was Europe’s undisputed center for art, music, theater, and every other entertainment morally acceptable or not.

His mother was the more successful of the two parents, and Giacomo would later claim that his real father was not Gaetano Casanova, but Michele Grimani, who was a very rich and powerful patron of theaters in Venice.

Grimani was also a nobleman, and that would have made a huge difference for Giacomo. The last century before the French Revolution was a general manifestation of noble power. Louis XV in France had inherited an immensely rich, and powerful (and corrupt) state from his grandfather the Sun King Louis XIV, and in Venice, everything from politics, and economics to justice and religion was in the hands of the nobles. With the title that Michele Grimani could have given him, many of the misfortunes that lay ahead could have been avoided.

Anyway, his official father, Gaetano, died in 1733, and with his mother often away touring with theater companies, the stability and guiding hand in the boy’s life became his grandmother, Marzia Baldissera in Farussi. She was his true caregiver much more than his parents.

Studies in Padova 1734 – 1741.

At nine, he was sent to Padova for further studies. The boarding house where he lived initially, was not to his liking.

– I was always hungry, he writes.

So instead he was accepted as a lodger with his primary instructor, Abbé Gozzi. As Gozzi, as well as Casanova’s mother, had hopes for Casanova to become an ecclesiastical lawyer, Giacomo studied law. Although his passion was much more towards medicine and science, he still pursued the path that was chosen for him. And maybe his most important quality was just that, the capacity to make himself liked by others. He was not only handsome, well-educated, and amiable, but he also did and said what was expected of him at the right time. He knew how to please.

He definitely knew how to please his tutor’s young sister, Bettina. She was a beautiful adolescent girl, and she immediately became young Giacomo’s preferred playmate. He later described her as his first love, as well as the one who lightened his passion for erotic adventures. He was only 11, and Bettina was older, so we don’t really know how ready he was for the occasion. He was, in fact, rejected. But he still treasured his relationship with both Bettina and her older brother for many years to come.

Casanova back in Venice, but sidetracked to Greece.

At only 16, he took his Bachelor’s degree in law (They learned quickly back then…). At that time, he was already well educated in Christian teachings, tonsured, and ready for a carrier as a cleric, a job that definitely wasn’t suited for him.

So he came back to Venice, and his beloved grandmother. His mother, Zanetta, was of less importance to the boy if we can trust his memoirs. But before beginning a structural and scheduled mature life, he decided to stop by at Corfu, an island close to the border between Albania and Greece. Corfu was a Venetian province so he was still within the Republic.

There he got into a fight with a French nobleman and had to flee head over heels in a small rowboat. On the open sea, he was picked up by a ship and brought to the town of Kassiopi on the northern side of the island. One could imagine that the situation would cause a certain degree of distress, being 16 years, without money, in a strange place, wanted by the police, and without friends or family within reach. But Casanova showed his extraordinary talent for survival by tieing bonds and making friends.

Within a few months, he had his own place at Kassiopi, a new extravagant wardrobe, important companions, and a beautiful fiancè.

One early morning, a French officer showed up to arrest the young rogue, take him back to Corfu Town and bring him to justice. Casanova was able to discover some irregularities in the Frenchman’s background though. Once back in Corfu Town he exposed him and was suddenly treated as a hero instead of a young scoundrel. He was pardoned and could continue his journey to Constantinople before he went back to Venice.

… Why Casanova wouldn’t have made a good priest.

His first experience as a preacher in the church of San Samuele didn’t go well. For the occasion, he chose to base his preaching on the Roman poet Orazio, a master of elegance and style, but unfortunately very much a pagan writer.

His second attempt was on March 19, 1741. At 4 p.m. he was to preach at the feast of Saint Joseph, the spouse of Saint Mary. That same day he was invited to have lunch with the very rich and influential Count of Montreal.

Casanova was very well prepared for the sermon, remembering his failure the last time. He had studied his text and he had memorized it perfectly. But being as nice and accommodating as he was, he didn’t reject any of the many dishes he was offered at the Count’s palace. Nor did he curb his taste for the delicious wine.

At 4.08 he came running in through the front door of San Samuele. He stumbled as he climbed the steps to the pulpit and once there he couldn’t reorganize his discourse. His wine-soaked brain didn’t respond, and his first phrases were incoherent. In front of him, the parishioners looked more amused for every tentative he made, and when he finally realized that he couldn’t remember one word of what he had memorized so thoroughly, they were giggling loudly.

He panicked, and fainted, half simulated, half true. They took him to the sacristy where he had to contemplate his future. Then and there he decided that the priesthood wasn’t for him.

Life in Venice and the death of his grandmother 1743 – 1746.

There are many stories about Casanova’s youth in Venice. Most of them include love and young women, married and not. But even away from romantic adventures, he seemed to have lived a life of a playboy, without any real path to follow.

In 1743 his beloved grandmother died, and his mother moved to a less luxurious flat with Giacomo and his four siblings. This had a profound impact on him, as it deprived him of his tutor and only real stability in Venice.

In 1743 he was also imprisoned for the first time, accused of immoral conduct. He served just a few months at Forte di Sant’Andrea.

In 1744 he went to Calabria, then to Naples and Rome.

In Ancona, one of his love stories included a Castrato, one of the male castrate singers who were much appreciated in Europe in the 1600s and 1700s. The Castrato in question was Bellino. He was from Bologna and Casanova offered him a passage to Rimini. Bellino accepted and during the trip, our young hero used every trick in the book to seduce him. When the fires of passion became unstoppable Casanova reached down to caress his lover’s genitals. The secret was revealed and just as he had expected all along, Bellini was no man, but a woman. Her name was Teresa, and the reason for her disguise was that the church didn’t accept female singers at its theaters. And the church was a very wealthy and powerful employer.

Meeting Matteo Bragadin 1746 – 1749.

On a very cold evening in January 1746, during Carnival, Giacomo saw a man in distress in a Gondola not too far from his. He didn’t hesitate but ordered the Gondolier to get closer, and with common efforts, they managed to stop the man from falling overboard. Casanova, who was somewhat knowledgeable in medicine helped him regain his consciousness and brought him safely to his home. Once there the man introduced himself as Matteo Bragadin, a Nobleman, and politician of importance in the Republic.

– You have saved my life. What can a do to compensate you, my young friend? he asked.

Claude Arnulphy-“Adélaïde de Gueidan et sa sœur au clavecin”. Cropped. Courtesy of Musée Granet under CC BY-SA 4.0

– All I have done is help a man in need, Casanova responded. It’s no more than any gentleman is required to do. To see you healthy and well is compensation enough.

Bragadin would become a sort of patron to Casanova. Their deep friendship would introduce him to many high society contexts and help him from dangers when those same contexts turned against him.

For example, he warned him about the State Inquisition in 1749 and suggested he leave Venice for a while to let things cool down.

Casanova was regarded as a depraved individual, especially by the church. Although the Republic didn’t always agree with the dogmatic Catholic church in matters of personal conduct, when it came to Casanova, they were definitely on the same page. Venice was a very depraved city in the 1700s, but young Giacomo stood out. And there were probably many powerful men who wanted him out of the way as he was a strong competitor for the ladies’ attention. Furthermore, he was a threat to their own wives and daughters. Better to keep him away or locked up.

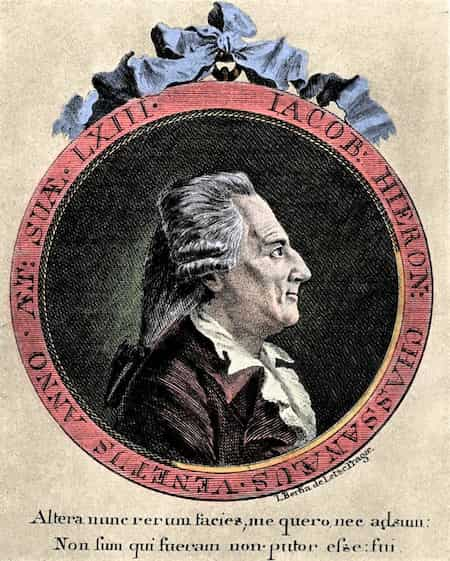

Meeting Adelaide de Gueidan in 1749.

Also in 1749, he met the love of his life. Yes, Casanova was a true lover. He was not just a seducer and collector of broken hearts. He respected and admired women, and he fell in love with just as much passion as if had been the one and only almost every time. This experience was different though and it had a profound effect on him as a man and as a human being.

He called her Henriette, but later historians have concluded that her real name was Adelaide de Gueidan, a French noble lady from Aix-en-Provence. They spent three months together, but she was destined to marry another man and couldn’t do anything to change that. When she left him, she wrote on the window with a diamond given to her by Casanova:

– You will forget Henriette too.

… But he never did.

His most famous achievement – The escape from Venice prison.

So, Casanova left Venice in 1749 but returned the year after. His restless soul wouldn’t submit to a normal, and stationary life in his hometown though. Almost immediately he set out again. This time to Paris, a city that was to become his second home. He stayed for two years in the French capital. Then he went to Vienna, then to Dresden, Prague, Milan, and almost every other reasonably important European city, before he foolishly return to Venice once again in 1755.

On arrival, he was placed under arrest, accused of the usual immoral behavior, and dishonoring the church. But this time, instead of the Garrison at Sant’Andrea he was sent to the “Piombi”.

The name means lead as it refers to the lead-covered roof of the Doge’s palace. The small prison cells were situated on the top floors with only the lead sheet between them and the burning sun. In winter they were dead cold, and in summer they were like an oven.

On top of that, Casanova’s cell was so tiny that he, with his 1,90 meters (6’2”) couldn’t stand straight. And there were rats as big as rabbits, and various unpleasant insects. But the worst of it all was that, according to Venetian praxis, nor the length of the sentence, nor the accusations were communicated to the prisoner. For all he knew, he could be there for life.

The first attempt.

In his desperation, he immediately started working out a plan to escape. Having found a long door bolt and being able to sharpen it to a chisel with a piece of marble, he slowly and methodically worked his way through the floor. It took him a full year and when he finally was ready to flee, he was suddenly transferred to another cell. Someone had betrayed him.

The new cell was bigger, lighter, and not on the top floor. But it was searched every day by the guards, so he couldn’t continue his digging. Instead, he again used his persuasive ways and made friends with a companion in the cell above his. He managed to send his metal tool to him inside a big illustrated bible with a plate of pasta on top to compensate for the added weight. and to prevent the messenger from opening the book.

The second attempt.

The prisoner in the neighboring cell, whose name was Father Marino Balbi, then slowly and methodically dug a hole between his cell and that of Giacomo Casanova. Once in Balbi’s quarters, the two men managed to break through the roof, and from there they crawled and dragged themselves threw a tiny window, over the attic, and down into a big lounge inside the Palace. Unfortunately, the doors were locked, and they were trapped. They collapsed on a couch and fell asleep.

Early the next morning, a servant opened the door. The two men woke up disoriented, but Casanova at once started screaming at the man:

– This is outrageous. A scandal. How is it possible that this can happen at the Doge’s palace? Are you responsible for this…?

Casanova in fact wore a dress in taffeta, at this point rugged and dirty, but still a sign of elegance. Being who he was, he had kept it for this occasion. And his companion was a priest and dressed as such.

Fate would have it that the evening before there had been a great ball at the Palace and the servant thought that what he had found were two unfortunate guests who had been locked inside one of the ballrooms by mistake.

– I am so sorry for the inconvenience, he said. Please, please don’t mention this to my superiors… Please I beg you…

And unknowingly he escorted the two gentlemen outside from the Palace and bade them farewell with compliments and reverence.

And Giacomo Casanova was a free man again.

Traveling the world: Paris 1756 – 1758.

That incredible story about his escape from “Il Pimbo” would become one of his most important deeds. Today we would call it viral. It was often the main attraction whenever Casanova was invited. Everybody wanted to know about how this fascinating man escaped one of the most feared and secure prisons in Europe, and they wanted to hear it from him in person. And he found himself famous and popular again.

As Venice was closed for him and would be so for 18 years he moved to the world’s political, and economic hub of the 18th century, Paris. François-Joachim de Pierre de Bernis had been the French ambassador but was now appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs in Paris. He knew Casanova well and introduced him to the Paris aristocracy.

In 1758 he planned and outlined a national lottery, to help restore the state finances after some of Louis XV’s disastrous affairs. The lottery was an enormous success, and Casanova was invited to the inner circles at the court. His popularity and fame had never been greater.

Reflections, meditation, and failures 1758 – 1774.

In the coming years, his desires very slowly changed. He was still the most exquisite, sociable, amiable, witty, and good-looking man in the known world, but something in his eyes had changed. Something was darker, more of an introvert… As if he was searching for something else.

He did services for France as a spy, he started an unsuccessful enterprise in import-export, and he courted a great number of women, some of which were married. And that’s when he finally met the one woman who he wasn’t able to have.

Her name was Marianna Charpillon, or more exactly, Auspurgher. A French daughter of a prostitute. She, herself, was in the same trade. Casanova met her in London.

– She had a face of an angel, chestnut hair, blue eyes, and a perfect, symmetric body. In short, I found her simply irresistible.

She was only 17 and Casanova almost 40. Her provoking ways and seducing manners made him completely lose control. But the more he courted her, gave her presents, flowers, jewelry, and declared her his love, the more she resisted him. It came to a point where he tried violence and brute force to get her, which resulted in accusations and a short stop in jail. Still, she wouldn’t budge.

Considering her profession, and the fact that Casanova couldn’t even buy her passion for money, while he could witness other men do just that, made a profound, and devastating impression on him. For the first time in his life, he felt beaten, defeated. And he decided to kill himself… Suicide from a broken heart.

As he stood on the side of the Themes ready to throw himself into the dark water, a friend called him from a distance…

– Hey Giacomo… Why don’t you come with me to have a few drinks together with these two ballet dancers?

And Casanova was saved.

He later bought a Parrot and trained it to say:

– Miss Marianna Charpillon is more of a whore than her mother.

Casanova back in Venice once again, 1778 – 1783.

Casanova met with most of the intellectual and cultural elite in 1700s Europe. He also knew many of the nobles and politicians. He knew Mozart, he met with Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Benjamin Franklin. He was a friend of Catherine the Great, Frederick of Prussia, as well as Madame de Pompadour, and Pope Benedict XIV.

But he still wasn’t a nobleman, and he had to trust his value as entertainment to be accepted into the high society of the 18th century. And as time went by the longing to see Venice again became ever stronger.

He finally succeeded in negotiating a pardon for the prison sentence, which actually never was very long in the first place. Something Casanova wasn’t aware of at the time of his prison break. He agreed to take the role of a spy for the Republic and served as such for a time in Trieste.

He stayed in Venice from 1774 to 1783, apart from when he traveled, which he did a lot. Times had changed though, and Casanova was older. Now he needed a way to cover the daily expenses. He worked as a theater impresario for a time, he started a monthly magazine, he translated the Iliad from Greek, and he wrote his own works. It was one of those, a short pamphlet criticizing the wrong person that finally got him banned from Venice for good.

He had found himself in a quarrel over money at the Palace of Michele Grimani. The opponent was a certain Carletti. What frustrated him wasn’t so much the insults by Carletti. He was quite used to that. What he couldn’t accept was that Grimani, a man he considered his biological father, took Carletti’s side. Casanova returned the favor, writing a short story dressed as Greek mythology. But anybody could see who the leading roles really were. And he practically said it out… He, Giacomo, was the son of Grimani, and more so, Grimani’s son was actually the offspring of another Venice nobleman by the name of Sebastiano Giustinian.

Well, he lost his most influential ally in the Republic.

And he probably seduced one or two of the ruling class’s wives and daughters as well.

He left Venice in 1783, never to return again.

And we’re back where we started – In Duchcov 1783 – 1798.

When he left Venice, he was almost sixty. His health was still good, but his capacity as a lover and socialite was considerably reduced. He felt old and the world he knew was slowly changing.

He went to Trieste. Then continued to Vienna where he stayed for a while working as a secretary for the Venetian ambassador. He reconnected with some of his old friends, but when the offer came to become a librarian at the Castle of Count Waldstein at Dux, Bohemia, he had kind of run out of options and accepted. His life as a rake was definitely over.

In Dux – Duchcov, he witnessed from a distance the French Revolution and the fall of the Venetian Republic. His world crumbled, and he died on June 4, 1798.

His last resting place is unknown.

Giacomo Casanova, the writer.

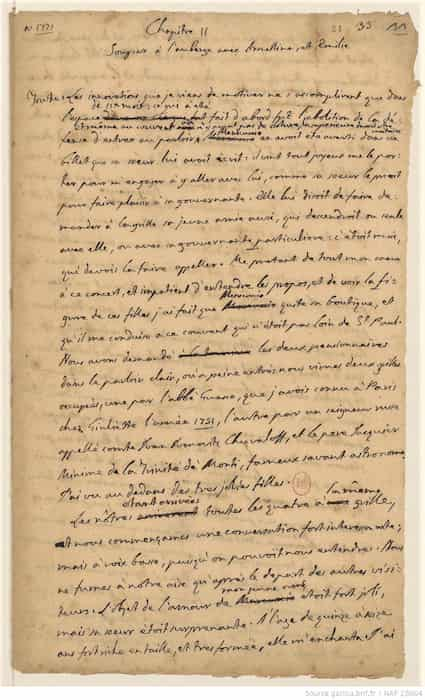

Although Casanova is known to the world as a master of seduction, his real value is that of a writer. He wrote a multitude of manuscripts of every sort, he translated, edited, and published. And it was mostly in that quality he made his living… As a storyteller.

Most Giacomo Casanova experts agree that there is a difference between when he’s writing from his own experience and when he’s not. And his by far most famous book is his memoirs. In Histoire de ma vie he takes the reader on a fantastic road trip through the 1700 society with a focus on female beauty and erotic attraction. And the reason for the natural language and flowing narrative was maybe that he didn’t write it for anyone to read it at all.

The memoirs were probably never meant to be published. That could also be one reason why they are so massive… 3700 pages, as well as the presence of quotidian details clotting its pages. He wrote them as a way to relive his many adventures, more for himself than for others to discover. It could even have been a suggestion from his doctor as a remedy against his melancholia, to write down his memories. It is written in French.

The book was published, heavily censored, in 1825 under the name Mèmoirs. The Catholic Church immediately put it on its list of forbidden literature, together with every other publication by the author.

- In 1960 (… After 170 years !) the first uncensored version was published.

- In 2010 National Library of France bought the original manuscript for 7,25 million euros. The seller was an anonymous heir to the publisher Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus. Histoire de ma vie is now considered a French national treasure.

- The narrative finishes in mid-sentence around 1774.

Apart from his memoirs, he wrote around twenty books, mostly after 1770.

Casanova – The greatest lover of all time.

The number of women he conquered range from 122 to 216 depending on who is counting. These are obviously not in any way exact calculations. Casanova didn’t finish his story, he probably didn’t mention everything about everything, and it was written at least 50 years after his first erotic encounter.

Let’s say 150 women in a lifetime.

A study in the US from 2004 concludes that about 1 in 5 American men have more than 20 sexual partners in a lifetime. Considering that Casanova never married and that he was incredibly desirable and didn’t seem to have had any problems in his conquests, 150 isn’t all that much. George Simenon, the Belgian writer famous for his books about the French detective Jules Maigret is said to have seduced 10.000 women. Rumors have it that Frank Sinatra made love to 5000 women. Like Piero Chiara, author of the book “Il Vero Casanova”, the true Casanova, said in an interview:

– I would say a normal Lifeguard at Rimini or Riccione (Italy) would have more women than that…

Giacomo Casanova wasn’t a conquerer just for the pleasure of it. He seems to have loved truly every time. He fell in love, sometimes deeply so, and suffered just like everybody does in the cruel and agonizing game of love.

As an example, he lived his days in Venice together with Francesca Buschini, a young lady without money or name. She was very much in love with the writer, and he with her. They lived together for a long period until Casanova was forced away from the lagoon city. From his many letters, we sense a touching ingenuity and tenderness, as well as a heart saddened by the fact that she wasn’t near. He actually continued paying for her for many years after he left Venice.

But the stories, the myths… Are they true?

Yes, it is reasonable to think that they are.

We have two ways to tell that at least most of it is, in fact, true.

- First of all, as I mentioned before, he probably didn’t write it to be published. It was a sort of diary, and the honesty in his words is noticeable. He doesn’t even try to put himself in a good light. His failures and defects are portrayed just as clearly as his success.

- The second thing to remember is that his adventures can be verified. And it has been verified. Countless experts have followed Casanova’s footprints all over Europe. Venice kept records of felonies, employment, business agreements, births, and deaths. And so did France. The travels, the enterprises, the books, even the escape from “I Piombi”, that is all true. What can’t be verified is what happened behind closed doors. His lovers are often named with only their initials, or with an alias. Still, they haven’t been difficult to identify. It is reasonable to think that what he tells us about his love affairs is mostly accurate. He just wouldn’t have much reason to exaggerate. In the State Archives of Venice, you can find documentation of the repairs made inside Casanova’s prison cell after the breakaway.

He lived his life to the fullest. Through his journeys, he saw most of France, Italy, Spain, Austria, Russia, Hungary, Checchia, and England. He met many of the most prominent men of the 18th century, and he loved and was loved by the most beautiful and fascinating women. Without being born noble, and without having accomplished great deeds in science, finance, or politics, he still counts as one of the most famous men of all time.

Giacomo Casanova, the world’s greatest lover.