How à became @.

As far back as in the early Venetian history, back when Venice was a small Byzantine province, the symbol à was used as at = at the rate of. The Venetian merchants would use it if they had to sell let’s say 500 units defined by weight or volume at 2 coins. The at in Venetian was written: à, with an accent on top.

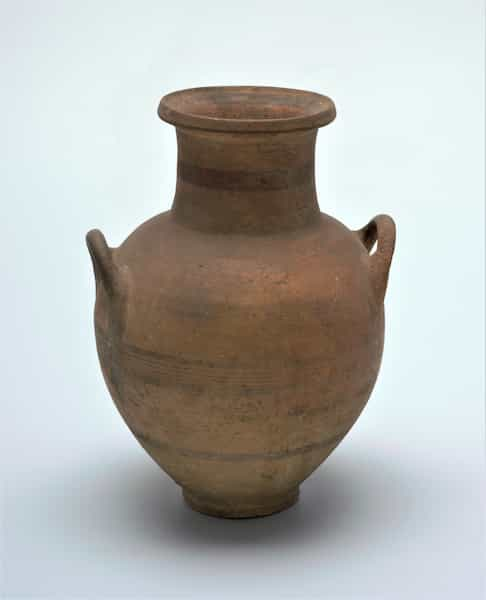

Much of their merchandise, both liquids and solids were sold in amphoras, a sort of big, ceramic, vase-like container. With time the Venetian traders found a way to simplify the use of the symbol. They took the accent over the a and made it round, to look a bit like the very amphora it was a symbol for. That way they could save ink and write just 500 @ 2.

What it meant back in the day.

The @ with the new, rounded form was useful as it meant a common, widespread unit with a common volume or weight. The Venetians traded very much with the eastern Mediterranean and in Arabic, the الربع (ar-rub) meant a quarter and it was abbreviated… Yes, with the @ symbol. Everyone could agree on quantities and weight without quarreling and disputing. It was a very practical symbol, and it meant smoother trading.

And although it was a Venetian invention, it wasn’t limited to Venice and the Arabic world. It was used from east to west, from Syria to Portugal. In fact today in Portuguese the word Arroba means roughly 15 kg of weight and is still used in Portugal and Spain as well as in many countries in South America in trading vocabulary.

How @ was saved from oblivion.

It continued to be used in a commercial context all the way until modern times. But the first typewriters didn’t include it. Maybe it was too complicated to carve out the @-type element in the 1800s machines. Or it was just a symbol that normal people never hit. Later versions of typewriters included it, but it was still a rare sight on paper. The usage was marginal.

In much the same way, the first tabulating machines wouldn’t include it. It was a technical commercial symbol with little application, and if the greatest invention of the 20th century after the washing machine hadn’t been born, maybe the @ would have been something we would see in historical documents only.

Because in the mid-1900 the first electronic computers entered the stage. And in 1971, the American computer technician Ray Tomlinson was sitting at his desk facing a delicate problem. He was working with a brand-new concept… Electronic post-service.

Computer technology had reached a point where single machines needed to be connected to others. The first attempt was called ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network). It was very modest compared to the modern Internet, but when e-mail was invented, it caught some traction. And it is with the creation of e-mail that @ went from being a never used symbol in a forgotten corner of the keyboard to a superhero in the virtual-media world.

The first ever e-mail.

The reason Ray Tomlinson chose @ for the e-mail address was very simple. He had to be able to address a message created by someone and sent through ARPANET to someone else on a different computer. He needed to separate the person’s name from the receiving computer’s name, and he needed a symbol that was rarely or never used in other circumstances to not confuse the program.

His eyes fell on the little strange curly thingy above the P. So, he wrote a simple e-mail to himself, from one side of the room to another computer on the other side of the same room. When it came through he knew the symbol was good, and he had made history.

The obscurity of the early history.

Studying history is a difficult task. if you want to prove what happened last week, it could be easy if you have some sort of documentation. Still, we all know that we often make mistakes about what people said, what happened, and what it all meant. If you go back thousands of years these mistakes often become huge.

The lives of Kings, Emperors, as well as wars and conquests are often well documented. But, simple farmers, shop owners, fishermen, Venetian traders, and such almost always do not leave anything close to written or documented for the future in any way. That’s why it can be easy to know if Nero, the Emperor lived in Rome, and we can be reasonably sure about his life in broad strokes. But it is extremely difficult to prove that Antonio the baker existed in the Roman Empire at the same time.

Having said that, someone could easily claim that I am wrong about the Venetian origin of @ because my proofs are somewhat fuzzy… And I am biased. But it’s still interesting, isn’t it?